Paul Revere Williams’ name is etched into the history of Los Angeles, not only as one of the 20th century’s most famous architects but also as the first African American to become a certified architect in the Western United States. His life is a story of overcoming prejudice, fighting for recognition, and believing in his own talent. Over his professional career, he designed more than 2,000 buildings, including homes for Hollywood stars, iconic public structures, and residential complexes that shaped the look of Southern California. More at i-los-angeles.

Biography

Paul Revere Williams was born on February 18, 1894, in Los Angeles to a middle-class family that had moved from Memphis seeking new opportunities. His childhood was tragic: his father died of tuberculosis in 1896, and his mother passed away two years later. The orphaned boys were taken in by the Clarkson family.

Williams studied at the Los Angeles School of Art and Design and later at the Beaux-Arts Institute of Design in New York. While working with landscape architect Wilbur Cook, he developed his understanding of space and composition. From 1916 to 1919, Paul studied architectural engineering at the University of Southern California (USC), where he designed residential projects even as a student. In 1921, he obtained his architectural license and became the first certified African American architect in California.

Paul Williams was married to Della Mae Givens. The couple had three children. His wife later founded the Wilfandel Club—the first African American women’s club in Los Angeles, which is still active today.

Professional Path

At just 25 years old, Paul Williams won his first architectural competition, and three years later, he opened his own practice. In 1923, he became the first African American member of the American Institute of Architects (AIA).

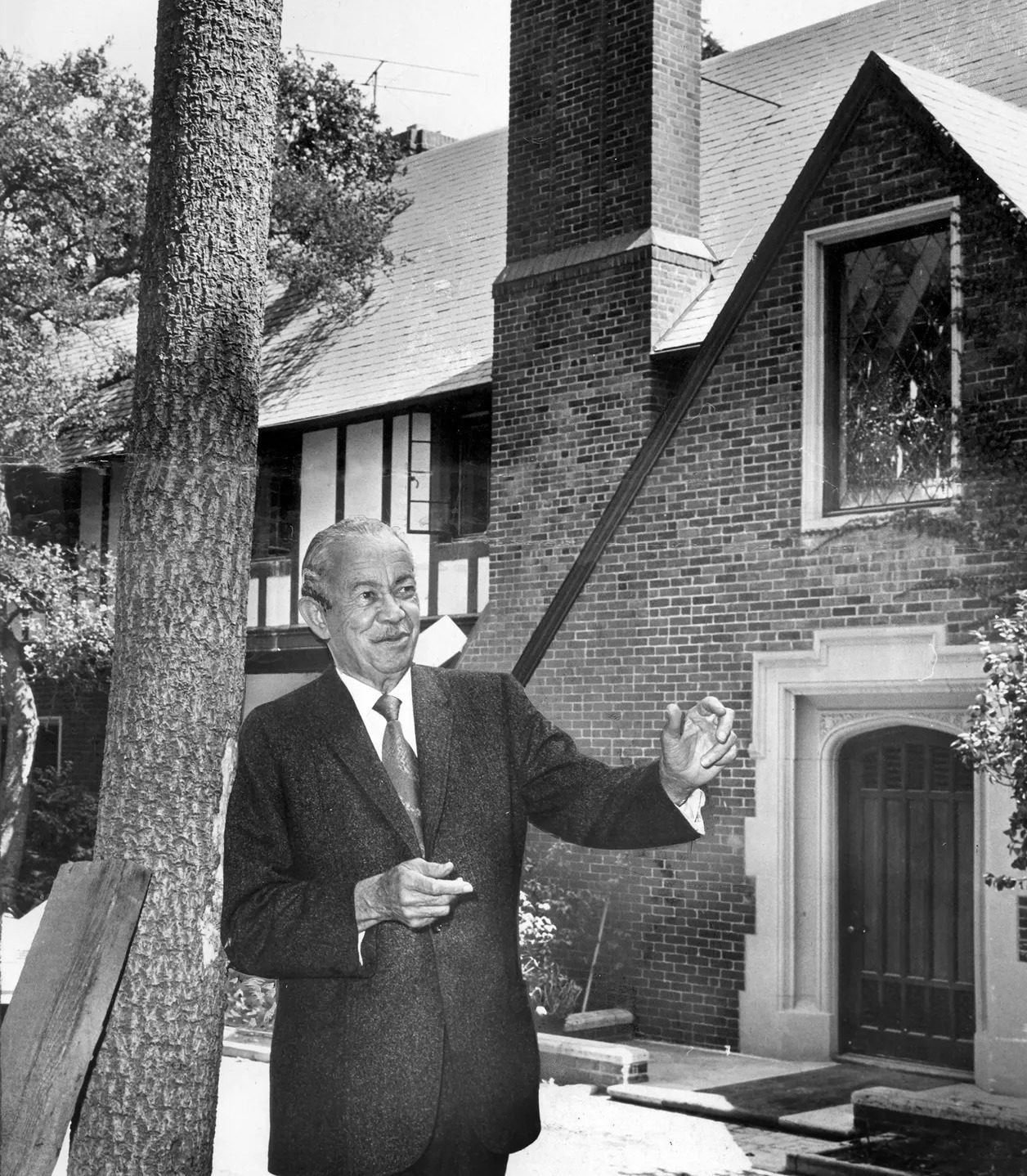

Williams worked on dozens of projects in Los Angeles, including the Beverly Hills Hotel, the Founder’s Church of Religious Science, the Angelus Funeral Home, and the Golden State Mutual Life Insurance Building, as well as public structures like Langston Terrace in Washington, D.C., and the Pueblo del Rio Housing Project in Los Angeles.

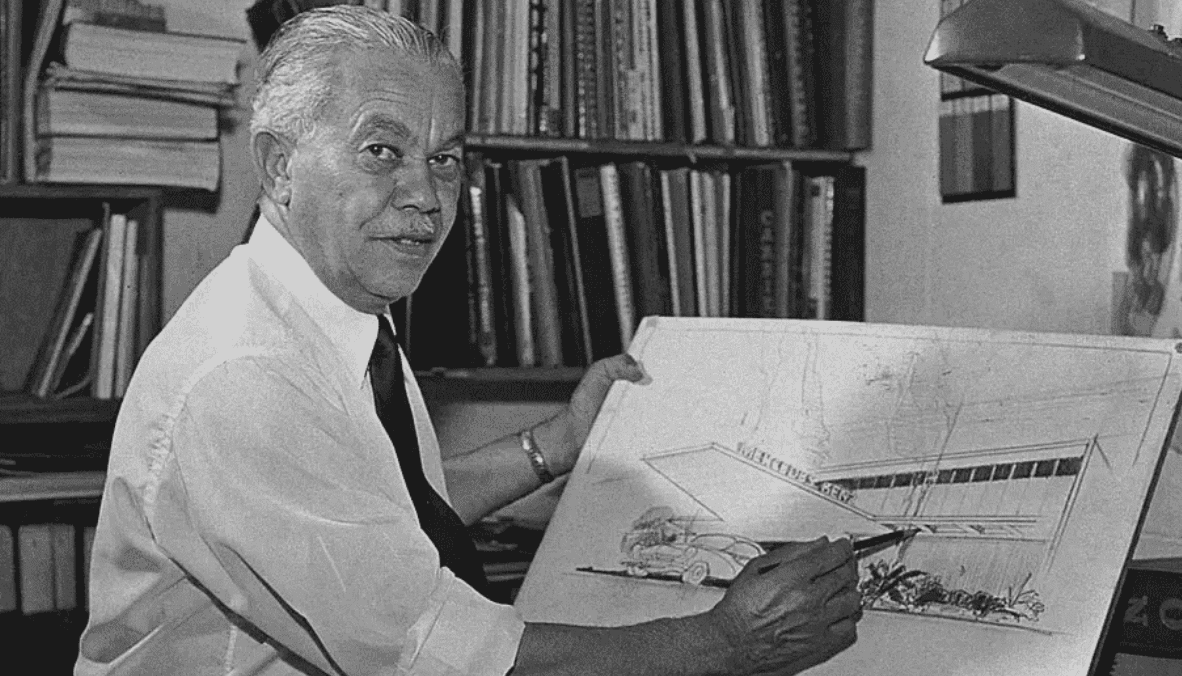

One of his famous innovations was a unique skill: the ability to sketch upside down, allowing clients sitting across from him to see his drawings right-side up. This technique became a symbol of his tact and professionalism at a time when racial prejudice was still the norm.

Williams was not only a practitioner but also an author of books that shaped the vision of residential architecture in post-war America. His works, “The Small Home of Tomorrow” (1945) and “New Homes for Today” (1946), offered innovative solutions for compact, comfortable, and functional middle-class housing. In an era when America was experiencing a building boom, his approach was a breakthrough. Williams emphasized that a home should not be a luxury but a space of dignity—accessible, harmonious, and full of light.

A special place in his legacy is held by his essay “I Am a Negro,” published in “American Magazine” in 1937. This text was a candid confession from an architect who had faced prejudice due to his skin color since childhood. Through his architecture, Williams created spaces that combined beauty with humanity. Through his writing, he reminded people that dignity does not depend on race, wealth, or social status.

Architect to the Stars

In the 1930s to 1950s, Paul Williams became a favorite of Hollywood stars. His clients included Frank Sinatra, Lucille Ball, Barbara Stanwyck, Tyrone Power, and Danny Thomas. His famous “pushbutton house” for Sinatra became a symbol of 1950s technological progress. At the same time, the architect dedicated attention to social projects. Among his works was Pueblo del Rio, one of the first federal housing complexes for the working-class population after World War II. While designing expensive mansions was his business, he considered social housing his passion.

He designed villas in French Chateau, Mediterranean Classical, and Art Deco styles. His famous Jay Paley House in Holmby Hills later became a filming location for the TV series “The Colbys.” During World War II, the architect worked for the U.S. Navy Department. After the war, he collaborated with Wallace Neff to develop experimental “Airform” houses—lightweight structures that could be built quickly with minimal materials.

In 1955, Paul Williams was commissioned to transform a former W.W. Woolworth store at the corner of Broadway and 45th Street in Los Angeles. He converted the new space into the Broadway Federal Savings and Loan Bank—an elegant, modern structure that reflected the spirit of the times and the financial independence of the African American community. When the bank opened, Williams stored a large portion of his professional documents there, including blueprints, contracts, sketches, and correspondence. This archive became a testament to an era when architecture combined aesthetics, technical skill, and a social mission.

During the 1992 Los Angeles riots, which erupted after the verdict in the Rodney King case, the Broadway Bank building burned down. Many believed that the architect’s documents—a significant part of the city’s modernist history—were lost forever in the fire. Fortunately, Williams’s family had been farsighted. His granddaughter, Karen E. Hudson, had carefully preserved most of the archive in private storage. Thanks to her efforts and the family’s decision, the archive was transferred for scholarly use to the Getty Research Institute and the USC School of Architecture.

His vision for space extended far beyond architecture—he even designed the Skylift Magi-Cab transportation system for Las Vegas, a concept similar to a monorail. In total, Williams designed over 2,000 buildings, dozens of which are listed on the U.S. National Register of Historic Places.

Paul Williams’s major works include:

- Saks Fifth Avenue, Beverly Hills (1939);

- MCA Building, Beverly Hills (1939);

- LAX Theme Building (1961, collaborative project);

- First AME Church, Los Angeles (1968);

- Golden State Mutual Life (1948);

- Jay Paley House, Holmby Hills (1935)

Recognition and Awards

Throughout his life, Paul Williams received numerous honors:

- NAACP Spingarn Medal (1953) for his contributions to architecture;

- Honorary doctorates from Lincoln University, Howard University, and Tuskegee Institute;

- AIA College of Fellows (1957)—the first African American to receive this honor.

The architect died on January 23, 1980, at the age of 85. He was buried in Inglewood Park Cemetery, near chapels he himself had designed. In 2015, a memorial plaza featuring a bas-relief of his most famous works was dedicated to Paul Williams in Los Angeles. His contribution was not forgotten after his death: in 2017, the AIA posthumously awarded him its Gold Medal—the highest honor in the world of architecture.

Paul Revere Williams was an architect who changed the face of Los Angeles and the perception of who could create architecture. His life is proof that talent, perseverance, and self-belief can break down any barrier. His legacy lives on, not just in forms of concrete and glass, but in the ideas of equality, dignity, and creative freedom.