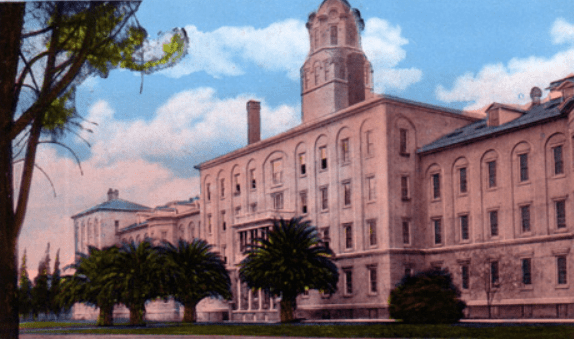

California’s early psychiatric institutions painted a stark picture of mental health and its treatment. The state’s first psychiatric hospital, the Stockton State Hospital, later known as the Stockton Developmental Center, operated from 1851 to 1995-1996. To delve deeper into the hospital’s history and its transformation into an educational campus, check out i-los-angeles.com.

The Story Behind California’s First Psychiatric Hospital

In 1851, Stockton, California, saw the establishment of its first hospital for the mentally ill. Captain Charles Maria Weber’s generous donation of 100 acres of land was pivotal, helping Stockton secure a state contract to open what was initially called the Stockton State Asylum for the Insane. While one might imagine local residents’ reservations about such a facility, Captain Weber was genuinely invested in the project, possibly driven by the promise of new jobs and economic benefits for the area.

At the time, hospitals simply weren’t equipped to handle the surge of people grappling with mental and emotional disorders. Many believed the California Gold Rush was a major culprit. During those frenzied years, gold seekers often faced moral decay, alcoholism, and even a certain “madness.” This dire situation created an urgent need for a specialized facility where those struggling with mental illness could receive proper care and treatment.

It’s worth noting that this was a significant leap forward. Before this, individuals with mental illnesses were often confined to private homes or even jails. Treatment typically involved isolation, physical restraint, and medications with severe side effects, like opiates and sedatives. Early approaches to mental health care focused primarily on maintaining safety and order, with little to no emphasis on individual therapy or rehabilitation.

Early Scandals Rock the Asylum

The hospital’s first superintendent, Dr. Reed, lost his position after a new governor was elected in 1856. Dr. Samuel Langdon, appointed as his successor, quickly accused Reed of abusing his power. Allegations included forcing patients to build his personal residence, underreporting patient deaths, and even using a single grave for multiple burials.

These accusations led to a dramatic court case, culminating in a duel in February 1857 between Dr. Langdon and Dr. Ryer, a staunch supporter of Dr. Reed.

Fortunately, no one was fatally wounded in the duel, and all charges against Dr. Reed were eventually dropped. Dr. Langdon’s tenure lasted only six months. This high-profile duel made headlines at the time, captivating the public.

An Inside Look: Life at Stockton State Asylum

Journalists have always sought out captivating stories, and readers will be intrigued by Frank A. Peltret of the “San Francisco Examiner.” He famously feigned insanity to gain admission to the California State Asylum for the Insane in Stockton and assess the patient experience. He was “rescued” from a marsh as a suicidal individual, examined, and promptly declared insane.

Peltret spent several weeks in the institution until a colleague secured his release. Afterward, he penned a revealing article, detailing his personal observations and experiences. What’s surprising is that it was a largely positive report. He even admitted to expecting a far worse situation at the hospital. He explained that such negative preconceptions often stemmed from distorted accounts by patients, who genuinely believed they were wrongly confined and that doctors and attendants were conspiring against them.

Despite his generally positive experience, Peltret still offered several recommendations to the hospital, including suggestions for diversifying patient activities, improving nutrition, and, importantly, advocating for more thorough patient supervision and enhanced staff training.

A Name Change and Noteworthy Patients

On May 17, 1853, the hospital was renamed the California State Insane Asylum under the leadership of Dr. Robert K. Reed, its first superintendent. It’s also worth noting that the hospital came under the control of the State Commission in Lunacy, established in 1897.

Examining the administrative history of the asylum reveals California’s attempts to integrate physical and mental health programs within a single Department of Health. However, these efforts proved detrimental, especially for patients with mental health needs.

In 1986, the Stockton State Hospital was rebranded as the Stockton Developmental Center.

Among the notable patients who resided at the psychiatric hospital were:

- Serial killer Carroll Edward “Eddie” Cole, an American serial murderer convicted of strangling women. He was executed in Nevada, and his brain was removed for anomaly research at the University of Nevada-Reno Medical School.

- California socialite Sarah Althea Hill. At 41, she was committed to the California State Mental Hospital in Stockton with a diagnosis of “dementia praecox.” Sarah Althea Hill remained institutionalized until the age of 86, when she died of pneumonia. She was spared burial on the hospital grounds and instead rests in the Terry family plot at the Stockton Rural Cemetery.

- Self-taught artist Martin Ramirez, who spent most of his life in California psychiatric hospitals after being diagnosed with catatonic schizophrenia.

- Lightweight boxing champion Adolphus Wolgast, also known as the “Michigan Wildcat.”

The California State Archives currently house over 130 bound volumes of textual records and more than 2,300 photographic prints, negatives, and slides related to the institution.

Evolving Approaches to Mental Healthcare

The treatment of mental health patients underwent significant changes over the years. In the 1800s, for instance, patients were often confined with iron chains and shackles. While these methods are long gone, the Mental Health America Association uses a bell symbol, cast from melted-down shackles in 1956, as a powerful reminder of this difficult past.

From 1929 to 1946, Margaret Smith served as the hospital’s superintendent. Disliking the terms “asylum” and “insane,” she successfully changed the institution’s name to Stockton State Hospital.

In 1953, the facility celebrated its 100th anniversary. At that time, 4,600 patients underwent procedures like lobotomies, electroshock therapy, and hydrotherapy. In the years that followed, the advent of antipsychotic medications revolutionized the treatment of mental illness forever.

The Legacy of a Landmark Institution

The Stockton Developmental Center closed its doors in 1995-1996 due to the reduction of state Developmental Centers, as outlined in the Coffelt Settlement Agreement (Governor’s Budget, 1996).

Despite its closure, the hospital’s legacy lives on. It holds the 1,016th spot on the California Office of Historic Preservation’s list of California Historical Landmarks, officially registered on March 10, 1995. This hospital made history as the state’s first psychiatric facility to embrace more progressive forms of treatment.

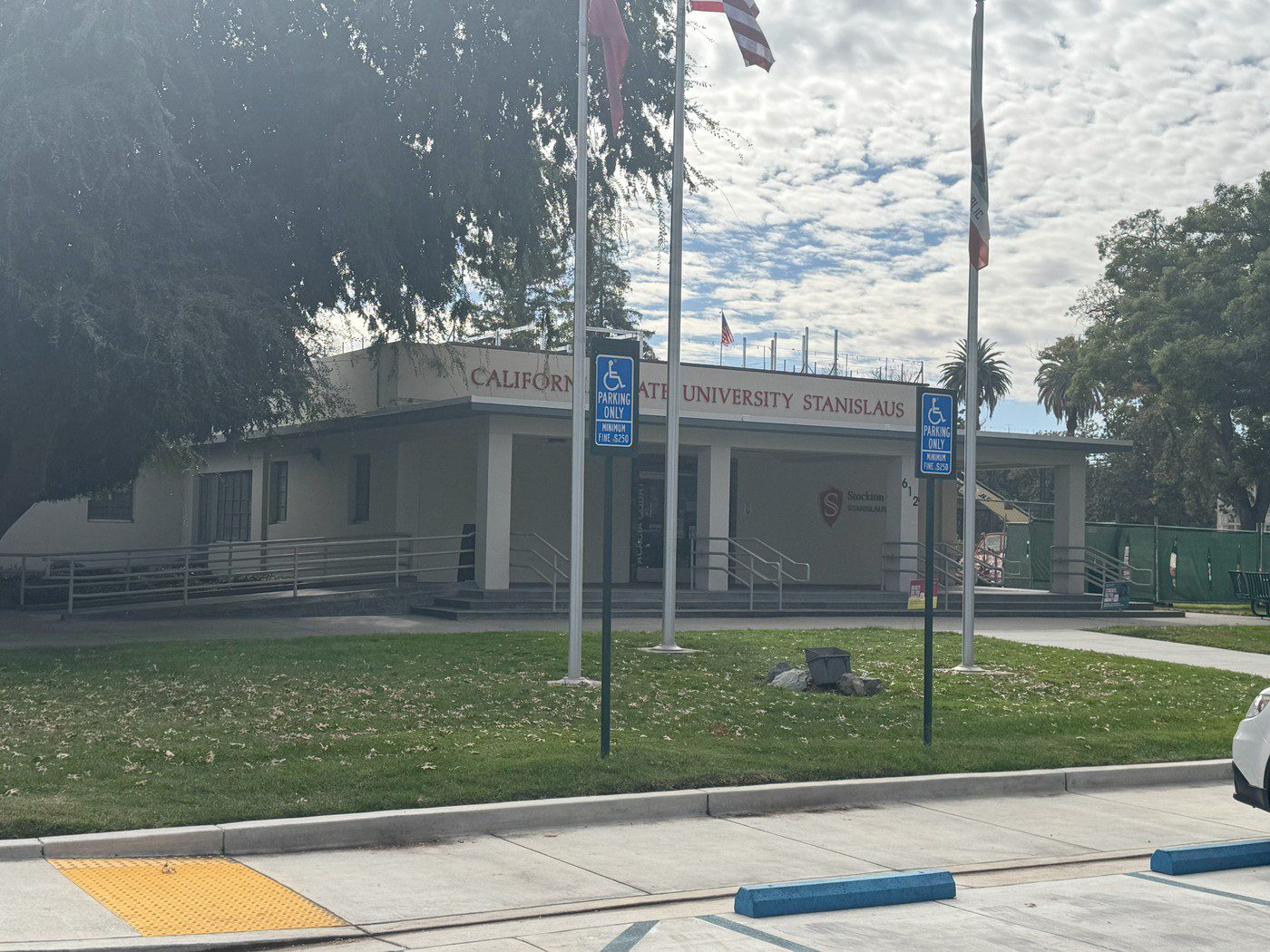

Today, the site is home to California State University’s Stanislaus – Stockton Campus. The campus also features a cemetery for patients who passed away while receiving care at the hospital.

Every historical account has its highs and lows. One lingering negative aspect is the perception of Stockton by its residents. There’s a subtle sense of disdain, perhaps stemming from the hospital’s presence, its eventual closure, and its overall impact on the city’s image.