Diseases, injuries and death often accompanied the indigenous inhabitants of Los Angeles. To combat them, city residents developed medicine with the help of local flora, the wisdom of traditional healers and their faith. Colonists from Spain and Mexico brought their own healing traditions. The first doctors and pharmacists of Los Angeles radically changed beliefs about diseases and their treatment. Read more at i-los-angeles.

On the border of three worldviews, medical care in Los Angeles until the 1850s was a mix of science and European and indigenous folk traditions. Fundamental changes have taken place in the field of medicine over the past two centuries. In the 21st century, innovative medical facilities operate in Los Angeles. Among them is Cedars-Sinai Medical Center.

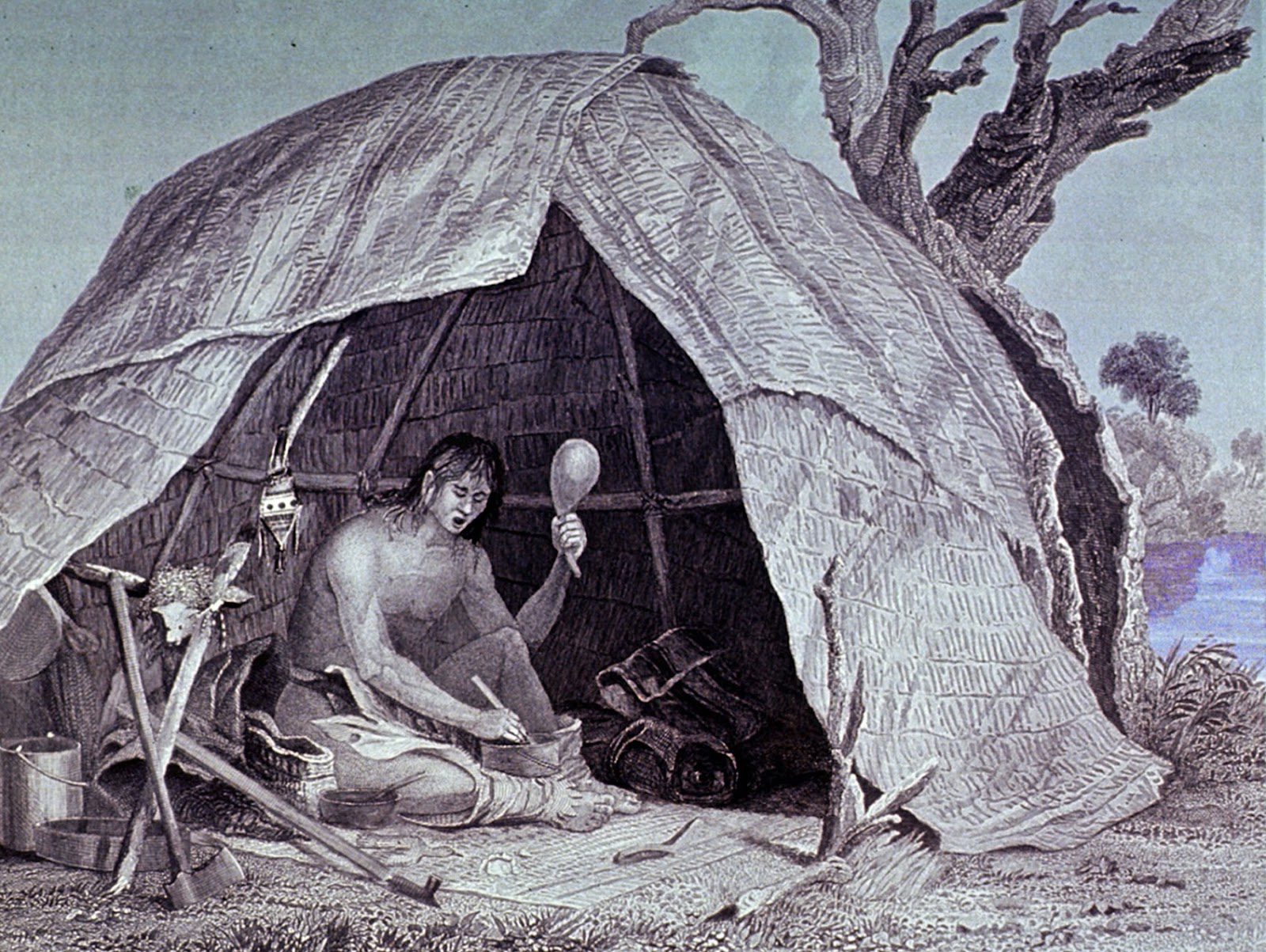

Precolonial Los Angeles

Rural healers scoured the hillsides in search of medicinal herbs. Lomatium californicum is an aromatic root that has both healing and magical properties. Townspeople carried it in their pocket to ward off rattlesnakes. To relieve headaches, healers advised chewing the root, while its decoction helped with indigestion. It was also believed that the leaves of California laurel (Umbellularia californica) cured headaches.

Pacific poison oak (Toxicodendron diversilobum) was dried and turned into powder, which was then used to cover wounds and cuts. A tea was made from Poison oak to treat diarrhea. Teas made from leaves and bark, as well as bloodletting therapy, helped residents of precolonial Los Angeles stay healthy.

Shamans used tobacco smoke, bloodletting and even red ants to treat both physical and emotional disorders through controlled dreams and narcotic-induced visions.

Colonial missions in Los Angeles

When the expedition crossed the plains of Los Angeles between 1769 and 1770, Juan Crespi noted the region’s strong health. Crespi was the first promoter of a healthy lifestyle in Southern California. However, the vibrant climate and cheerful residents hide a history of endemic diseases, including tuberculosis and bacterial infections, which reached the Los Angeles grounds from Mexico and Central America. Other diseases, such as measles, smallpox and cholera, may have been passed on during interactions with Spanish sailors and English pirates.

The California mission system, initiated by Junipero Serra in 1769, was a medical catastrophe. Residents were then denied access to conventional therapy. Hundreds of people died from diseases such as measles, smallpox, dysentery, flu, typhoid fever, tuberculosis and pneumonia.

Each mission had an infirmary for the sick. Some missions also had a caretaker whose medical expertise was hardly better than that of the Native Americans. Such a caretaker treated ailments with tea and herbs. However, not all treatment methods during the colonial period were so inadequate. For example, the first vaccinations against smallpox began as early as 1786 in Monterey.

What led to the demographic collapse?

By 1820, a demographic collapse occurred due to European diseases. Syphilis, gonorrhea and despair led to a sharp drop in birth rates among the neophytes. By 1826, the birth rate among young women living in Mission Santa Barbara had decreased by less than half compared to the 1780s. Infant and child mortality increased while the number of births declined.

Missionaries concluded that California’s climate produced the sickly, weak and despondent people. There was a shortage of doctors. From the 1770s to 1823, only 14 physicians were sent to California to examine the health of the mission neophytes.

During the 1844 measles outbreak, the council issued a list of health regulations that included refraining from consuming pepper and spices, washing salted meat, taking a shower at least once every eight days and burning wax on a hot iron. The council also ordered people to self-isolate for three days after the first symptoms or contact with the sick. Only quarantine would have any impact on disease spread.

Most city residents were working-class and ranch families who could not afford doctor fees. Instead of professional care, most families treated the disease with traditional remedies. Every mother had a well-equipped medicine box. Surgery was also very primitive. Operations had to be performed at home. Modern scientific instruments and devices to support immunity or combat active disease were hardly available.

What were the treatments in the 19th century?

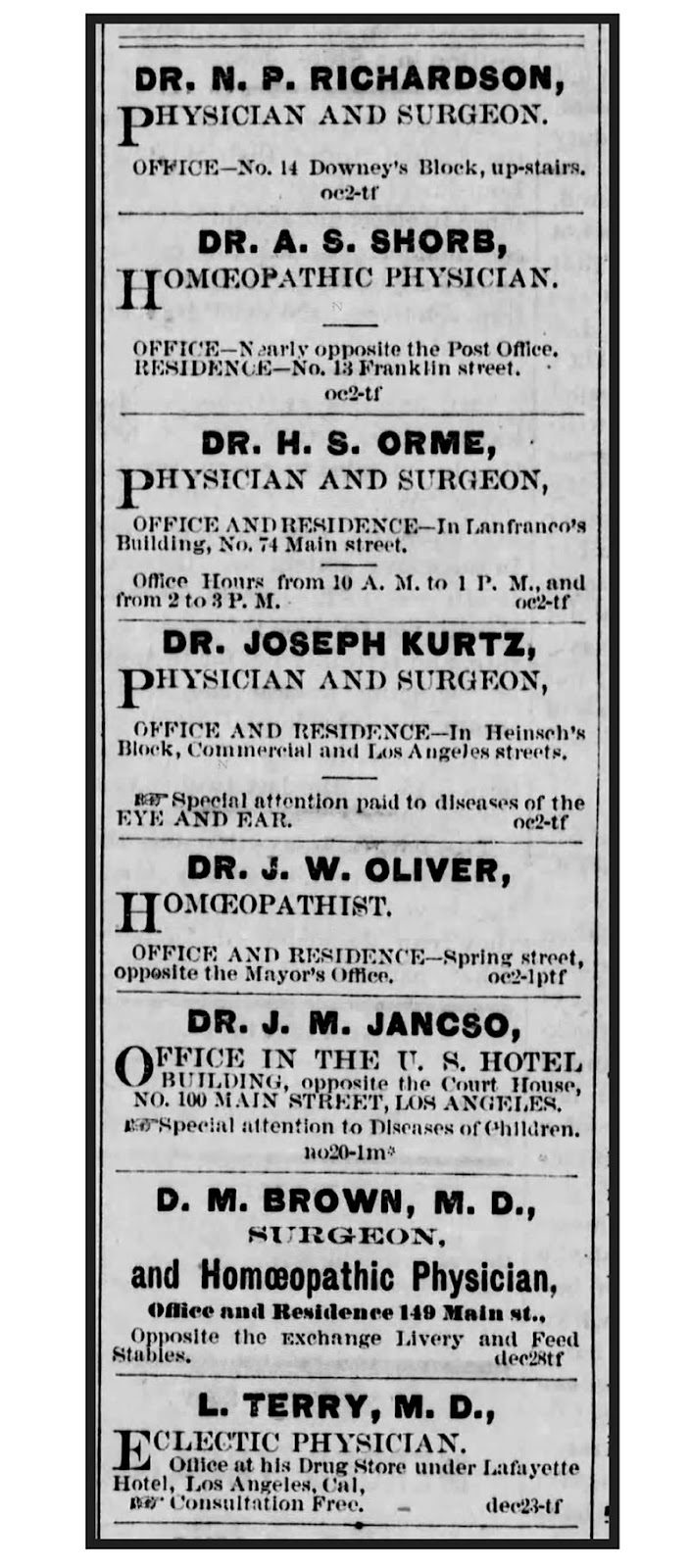

Medical practice in 19th-century Los Angeles was based on drugs and surgery. Patients could also turn to homeopathic practitioners and doctors who applied various approaches to illness. It was called “eclectic medicine.”

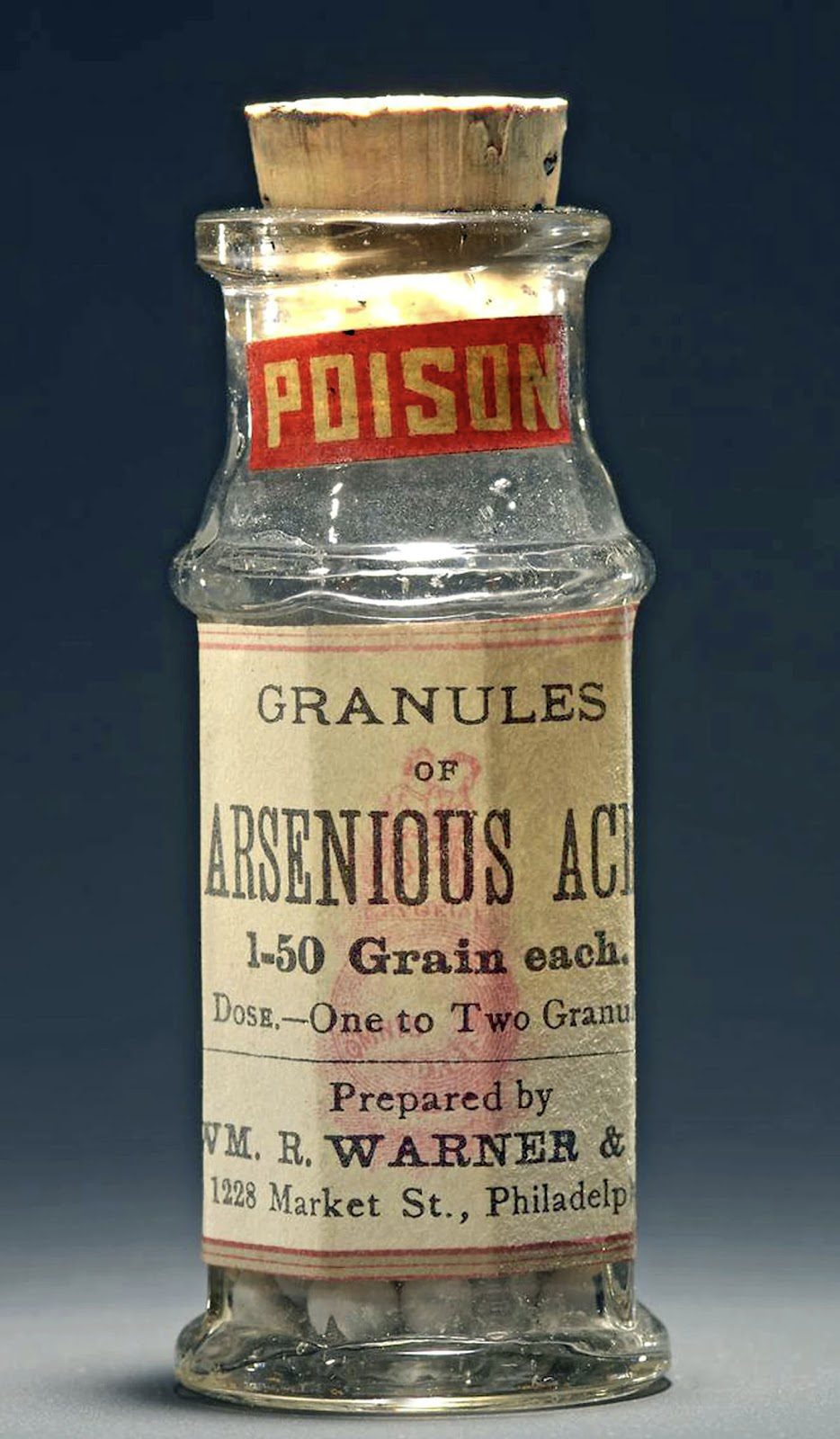

In the 19th century, doctors sold calomel to treat cholera, fever and stomach ache. Lead acetate was another toxic remedy for intestinal complaints. “Blue Mass” pills typically contained about 33% mercury and were prescribed for tuberculosis, constipation, toothache, parasitic invasions, venereal diseases, childbirth pains and depression.

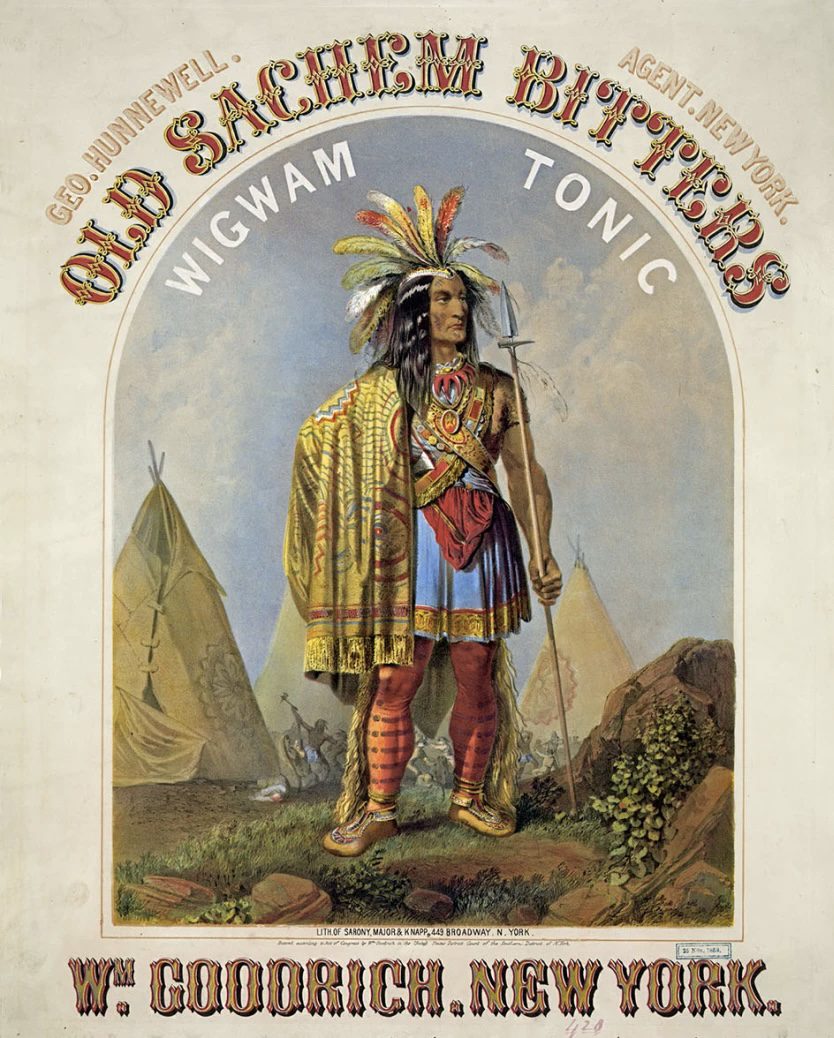

When new patented medicines emerged in the 1860s, townspeople still treated themselves with herbal and root tinctures or tonics with opium or morphine, which were mixed with a small amount of alcohol. Less toxic remedies included pungent herb for bronchitis, coughs and flu, peppermint oil for intestinal upsets, clove oil for toothache relief, camphor for pain and itching and cayenne (red pepper) as a lotion to reduce arthritis pain.

Medicines containing mercury and herbal decoctions caused physical effects that sufferers sought to reach. Sometimes, these effects were accompanied by pain that could only be alleviated with opioids. Doctors understood why their patients wanted quick-relief medications and that they could be harmful. So, physicians and patients began to think about Southern California as a remedy against a disease that does not have adverse effects of drugs. Patients with malaria were advised to live on the beach, while asthmatics were recommended to breathe the air from the nearby tar pits or mountain pines. Nervous prostration that arose from an overwrought nervous system was healed by Los Angeles’ air and sun.

Missionaries and Spanish colonial officials considered Southern California in the 18th century a highly unhealthy place, which explained the degraded state of the region’s indigenous inhabitants. Doctors in the mid-19th century said that Southern California was detrimental for Native Americans and mixed-race Latin Americans but could help Americans who had tuberculosis, chronic illnesses or nervous exhaustion. Doctors successfully promoted the idea that crippled office workers and traumatized Civil War veterans recovered thanks to the sunlight of Los Angeles.